Decarbonisation in pharma and healthcare: State of the sector 2025 report

by Simon Hodgson, Marion Briggs, Lee Jukes, Claire Carter

View post

This is Part 1 of a three-part series on making mining (or any industry with environmental liabilities) more sustainable by leveraging financial mechanisms. These articles will explore how the influence of money and law can be harnessed to promote ethical practices while simultaneously saving money.

With a growing number of mines reaching closure and seeing closure costs materialize, regulators, lenders, and banks are observing projects that fail economically by miscalculating the cost to close their site(s). In Canada, mining projects are subject to both provincial/federal environmental and mining legislation. Generally, provincial or territorial legislation sets the requirements for the tailings storage facility and the storage of waste rock and other waste products. Additionally, federal legislation typically sets the requirements for effluent discharge, navigable waters, fish-bearing water and fisheries, and matters on federal lands.

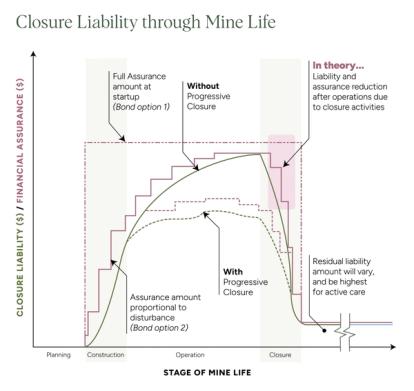

Since the 1990s, a mine closure plan is required by law in Canada, and mining companies, owners or license holders must also provide financial assurance (i.e., closure security or bond), to ensure that appropriate funding is available for executing the plan prior to starting work. The closure security is in place in the case of abandonment where the government would have to take on the liability. Certain jurisdictions require the closure plan to be filed prior to any exploration activities being undertaken and the plan may be subject to contaminated site remediation obligations.

As the closure plan is considered a living document that is reviewed and updated periodically to reflect mine and legislation changes, the closure guidelines are well documented:

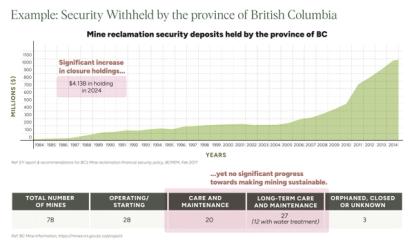

Despite all the measures, the number of mines that have been fully closed in Canada is relatively small. Most of the inactive, unclosed mines are operating under “care and maintenance” conditions or classified as orphaned or abandoned.

Abandoned Mine: no active mining claims or leases and where the owner responsible for the mine no longer exists or cannot be found.

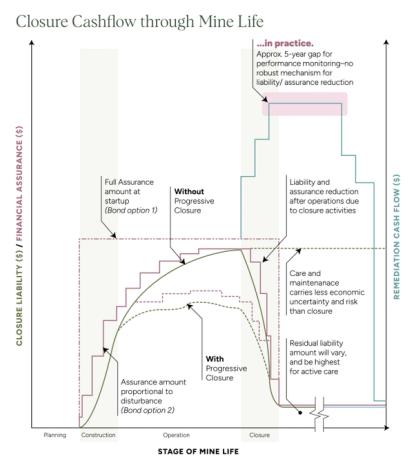

The goal of the closure security is to ensure the responsible government agency can use it to close the site in the event of abandonment. The cost of government-run mine closure activities after abandonment is often more than the amount available. This overrun could be due to several factors, including but not limited to:

Realistically, the most effective way to close mines would be to have the owners close their own sites. Mining companies should be encouraged to advance their inactive properties from care and maintenance to active closure. A major issue for mining companies is the lack of reliable ways to release the security, which can lead to additional closure costs. British Columbia, one of the largest mining jurisdictions in Canada, held CAD $4.13 billion in security for active and inactive mines in 2025.

This pool of credit should motivate mining companies to close their properties to reclaim their funds.

However, the process to release this security is complicated. Often, the full amount is held until all post-closure conditions are met, which can take a very long time. The length of the observation period required to ensure closure stability practically ensures the securities will be held indefinitely.

Without clear criteria and release mechanisms, companies are reluctant to invest more money in closing their mines.

In Part 2 of this series, we will explore strategies for releasing the funds needed for closure.